Christian Folk Art in Early America

A look at how Christian themes appeared in homes, churches, and workshops.

Edward Hicks and The Peaceable Kingdom

In Pennsylvania almost two hundred years ago, a Quaker preacher named Edward Hicks spent his evenings painting the same scene again and again. Lions, lambs, oxen, and children stood side by side under a calm sky. In the distance, William Penn made peace with the Lenape people. Hicks called it The Peaceable Kingdom, and he painted more than sixty versions.

He wasn’t chasing perfection. He was trying to understand a verse from Isaiah: “The wolf shall dwell with the lamb.” His animals look uneasy, their eyes wide, as if the world hasn’t quite learned how to live in peace. That tension made the paintings honest. Hicks’s faith was not an idea on paper but something he worked out through brush and color.

One version now hangs in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Another is in the National Gallery of Art. They stand as reminders of how personal and spiritual creativity often overlap.

Early American Folk Painters and Their Bible Scenes

Many early American painters who depicted biblical stories were not trained artists. They were farmers, carpenters, or schoolteachers who painted in their spare hours. They made their own pigments from clay, soot, or plants. Their materials were as plain as their meeting houses.

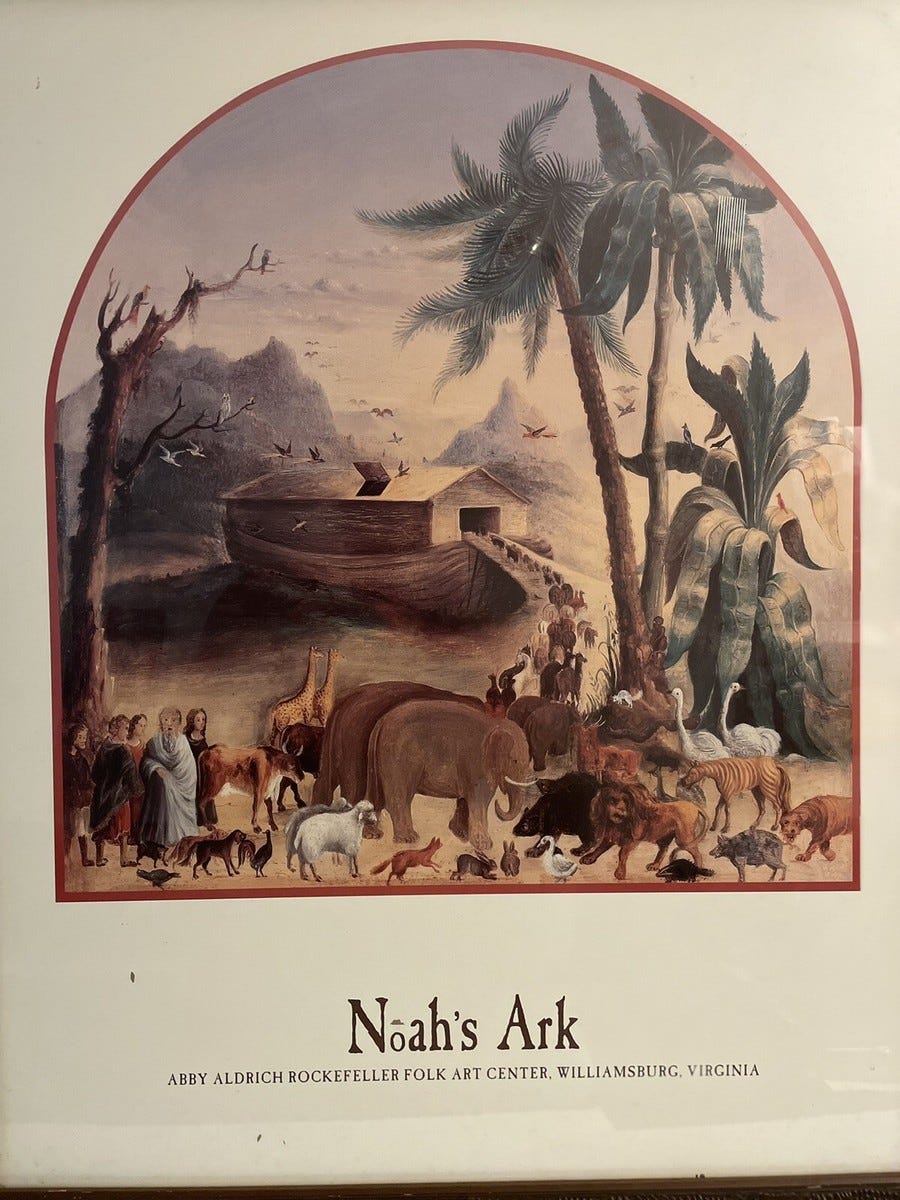

You can still find examples in the collections of the American Folk Art Museum in New York and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Virginia. Noah’s Ark appears often, its steady lines and balanced shapes speaking to order after chaos. Jonah and the Whale was another favorite, painted on wooden boxes or church walls. These works were made for homes and small congregations. They were part of life, not separate from it.

Shaker Vision Drawings and Gift Paintings (1830s–1850s)

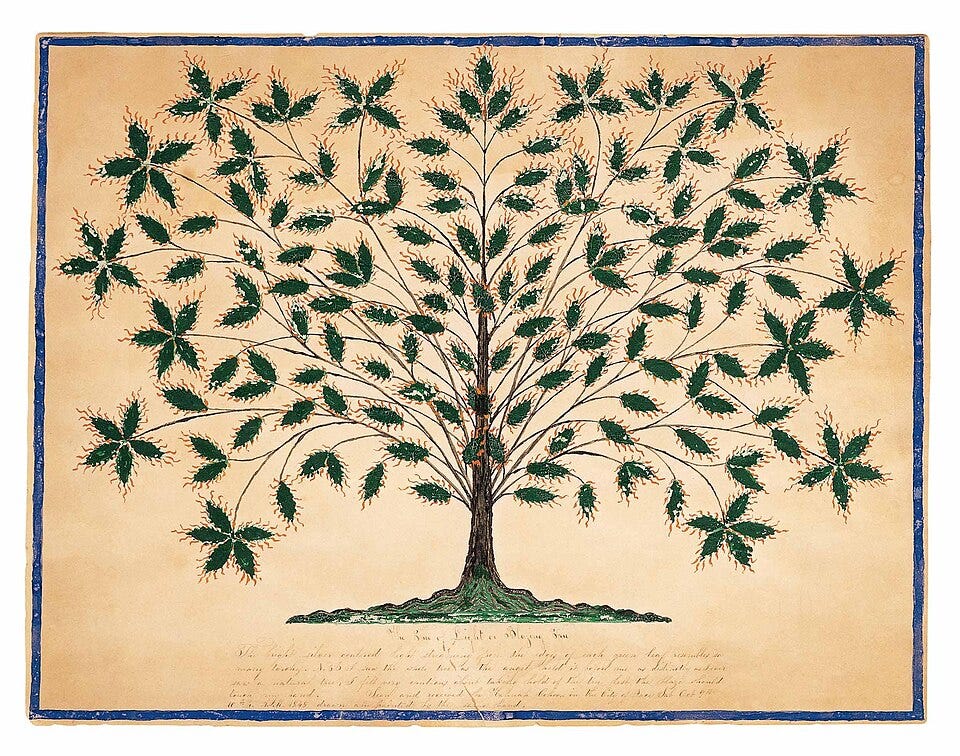

The Shakers, known for their disciplined and communal way of life, believed that art could be a form of revelation. Between the 1830s and 1850s, Shaker women produced drawings they said were inspired by divine visions.

One well-known example is Tree of Life by Hannah Cohoon from 1845, now held at Hancock Shaker Village in Massachusetts. The drawing shows a strong trunk rising upward, its branches filled with stars and doves. Cohoon said the vision was given to her during prayer.

Local Faith: Fraktur Certificates and Appalachian Paintings

As the country grew, artists began setting Christian stories within familiar landscapes. An anonymous Appalachian painter placed Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane among rolling hills that look more like Tennessee than Jerusalem. The background makes the story local and real rather than distant.

In Pennsylvania, Fraktur birth and baptism certificates joined Scripture with decoration. They often included verses, flowers, and birds around the name of a newborn. The Winterthur Museum in Delaware holds several examples from the late 1700s and early 1800s. Each one turns a family record into a statement of faith.

Folk depictions of the Crucifixion made by enslaved and newly freed African American artisans in the South survive as carvings in wood. Their work joined belief and endurance, showing Christ’s suffering as something shared and redemptive.

William Edmondson and Stone Carvings in the 1930s

In the 1930s, William Edmondson, a former stone mason in Nashville, said that God told him to begin carving. He worked with pieces of discarded limestone, shaping angels, preachers, and headstones. Edmondson had no training. He said his ideas came to him through prayer.

Today his sculptures are preserved in the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Cheekwood Estate in Tennessee. Each piece has the same solid form and sense of peace. Edmondson once said, “I can see the figures in the stone before I start.” His art carried on the same spirit that had moved Hicks and the Shakers: faith expressed through ordinary work.

Horace Pippin and Twentieth-Century Folk Painters

Later artists continued to paint with that same directness of belief. Horace Pippin, a self-taught painter and veteran of World War I, painted both religious scenes and everyday life. In his Holy Mountain series, completed in the 1940s and now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, he reimagined the peaceable kingdom for a world scarred by war and segregation.

Where Folk Religious Art Lives Today

Much of this work is now kept in museums or private collections. The American Folk Art Museum in New York City preserves many of the best examples, including Hicks’s and Shaker drawings. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Winterthur Museum all maintain collections that document how belief shaped early American creativity.

Outside museums, smaller pieces often appear in local historical societies, small-town churches, or family attics. Their condition varies, but their intent remains clear. They were made in gratitude and faith, not for recognition.

Looking at them today, we see a record of spiritual life that was personal, practical, and sincere.

Conclusion: Faith Made by Hand

You might still see one of these paintings in a small-town church or an antique shop, a faded Peaceable Kingdom print, a hand-lettered verse, a carved dove. Even in their wear, they hold something steady: the belief that the divine is close at hand.

When Jesus said, “The Kingdom of God is within you,” He was speaking to people who built and made things, who trusted that heaven could begin here if we let it. The folk artists of America took that seriously. They did not have marble or gold leaf, but they had time, patience, and faith, as do we.

Their work is a reminder that faith does not need a cathedral. Sometimes a brush, a plank of wood, and the will to make something honest are enough. The same lesson we can apply as a writer here on Substack, and our daily life as a reader.

We do not need anything but our minds to lead a good life, and to create a good life for those around us.